Plastiboo's VERMIS I Review

The Revenge of LoFi and Return of Japanese Nineties Aesthetics. @arcane_sword

Italian comics and graphic ephemera publisher Hollow Press tend to publish material that challenges us with images of the grotesque, profane, and unsettling, and in turn, cleaves into our psyche in pleasantly destabilizing ways. VERMIS I is no different in spirit, but certainly in form. The enigmatic artist Plastiboo’s graphic mock-adventure has sold thousands of copies, often selling out within hours, and has just ended its fifth printing of the arcane and lo-fi text that is VERMIS I. The book does multiple things simultaneously. At once, it is a mock game strategy guide, comic, and a part of a return to lo-fi aesthetics that harkens to the popular art-disrupting images of late 90s Japanese video games and their received images. To make matters more interesting, Plastiboo released a Spotify soundtrack that can accompany you during your descent into their particular Hell-adjacent storyworld where sounds further immerse you into the text. VERMIS I captures, in part, what separates good from great work; namely, it revitalizes what we know and expect by re-presenting the old in new ways again, undigested yet evolved.

The reading experience of VERMIS I is unlike anything I’ve read in some time. The mere fact that the work is a guide for a game that does not exist makes porous the thing that gives us distance from comics, film, or other media: diegesis. The refrain that has often been quoted on social media appears on the back cover of VERMIS I, “Which flesh is your flesh?” is not only a disturbing inquiry that calls into question one’s bodily identity in the book’s storyworld, it is a rhetorical and thought-provoking attack on our senses. The question echoes the work VERMIS I seeks to do to its reader: make us reconsider where a piece of art ends, where we begin, and where the artist might be located. These diegetic questions ask us to put aside for a moment the fact that the game it is guiding us through does not exist and to immerse ourselves, perhaps even lose ourselves in the arcane words and visuals Plastiboo presents to us.

It’s self-evident from my perspective that Plastiboo is in some way a part of a wave in popular art that possesses two spheres of aesthetics that have been capturing attention across culture for the last twenty-five odd years: Japanese popular art and the fantasy genre. Their dialectical relationship is expressed in numerous ways and mediums. Still, in VERMIS I Plastiboo is able to recontextualize both Japanese-inspired art and fantasy in a way that privileges the image and our relationship to it. Again, by asking “Which flesh is your flesh?” belies a more profound gesture. By Plastiboo themselves being enigmatic and therefore blurring our vision of them as artist and creator, while at the same time giving us images in the text that are lo-fi in style, and no straightforward story except the one we decide to tell ourselves as Plastiboo’s words operate as our Virgil in his ever-liminal book we—I, begin to feel that gesture of identity destabilizing art.

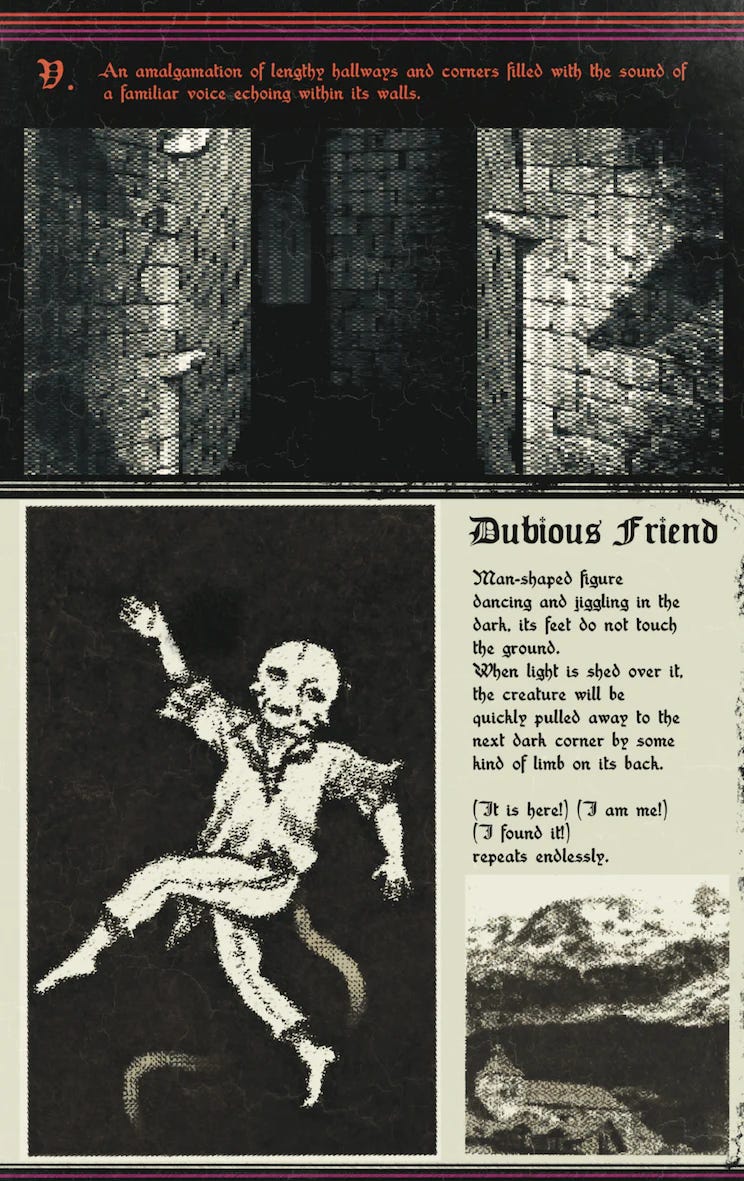

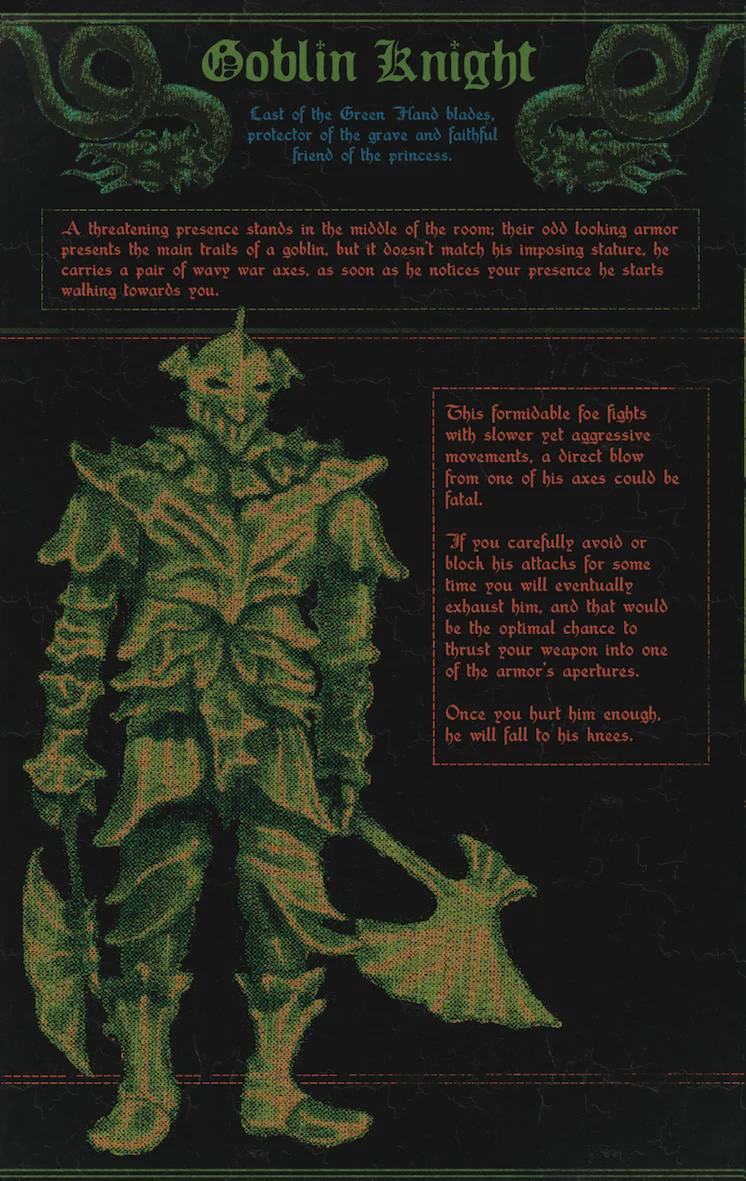

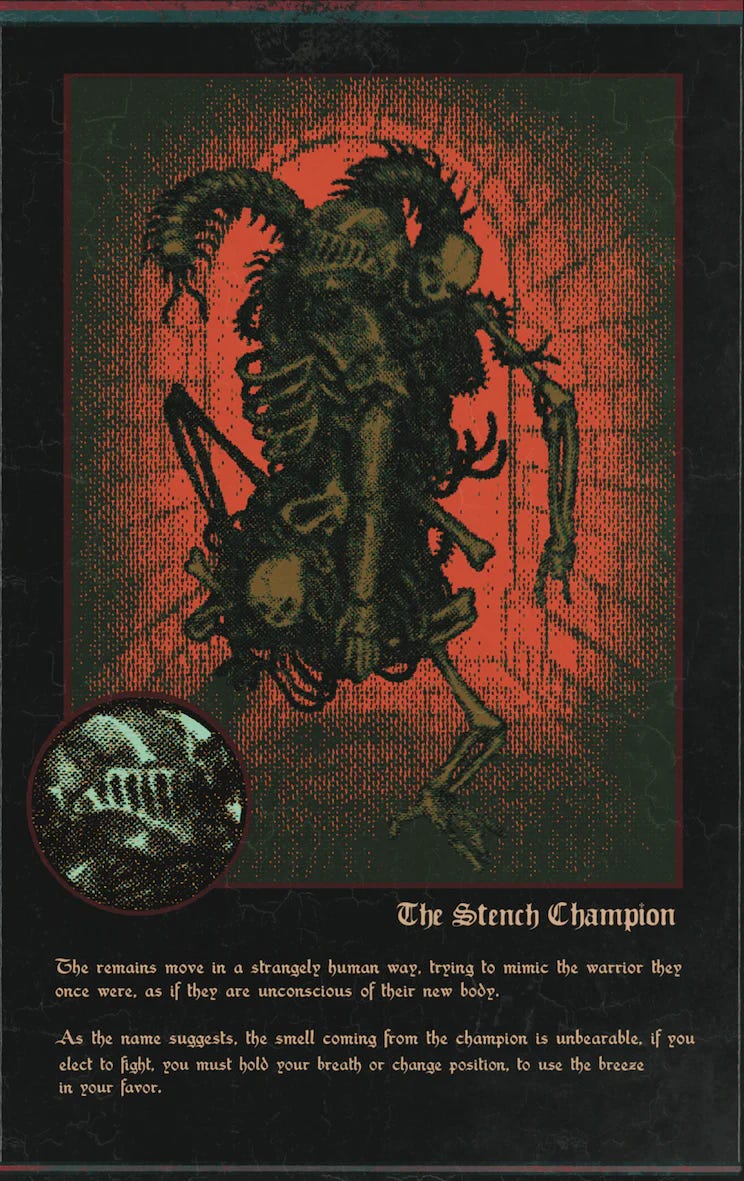

The artwork is nothing less than stunning. The intentionally lo-fi, low-resolution visuals of the book serve as a haze that the reader is never quite released from until the end of the story. The opacity of the monsters, particularly the character designs, offers those McCloudian gaps wherein we can inject ourselves. Are we monsters? Are we knights? Where does our flesh begin indeed? The way in which the book’s menu is laid out is an interesting resignification of the comic panel. Since, as all things VERMIS I and Plastiboo tend to be, play with our received notions of comics and menus by casting them as both highlights of the liminality of the work itself and constantly existing in-between, as, and both. This unresolved tension only heightens the stakes of each image in the book whether or not the image is meant to be kinetic. The kinesis itself is low, just as the resolution and fidelity are; and yet, that doesn’t rob any of the monsters or scares found within VERMIS I of their force or dread. Plastiboo only grants us a release we do not want from his purgatory on the last page of the text. An un-wanting developed in VERMIS I’s surprising moments of tenderness.

—JD